Her heart fluttered as they left the motorway. Five miles to go.

Five miles until daddy abandoned her.

Five miles until the horror began again.

The heavy wrought iron gates were the same, of course, although covered in a fresh coat of black paint. They always used to be kept closed, she recalled. (To stop the girls from escaping, it occurred to her to wonder?).

They were open now, but the notice on the wall had changed. No longer proclaiming a welcome to Stonehall Ladies’ College.

She wondered how many of the other girls had been brought back – as ‘treats’ by their lovers? Dared to explore the delights of the recently re-opened, press-acclaimed, ever-so-grand Stonehall Manor Hotel. ‘Your luxurious, care-free country bolthole’, as it described itself proudly in the glossy press ads.

Care-free?

The long parade of oak trees lining the drive were a few feet taller. The desire to open the door of the moving car, to jump out, to plead to be taken back to safety, love, comfort: that remained unchanged.

Tom wasn’t to have known, of course, that the demons that she’d taken such pains to chase away would have heard news of her imminent return and grinned their evil grins: “Coming back, my dear? Coming home?”

And he’d have been mortified, had he known. Tom, dear sweet Tom. Strong Tom, dependable Tom, caring Tom. Devoted Tom. So unlike the succession of assorted bastards, turncoats, svelte liars and needy-but-instantly-regrettable-fumbles who’d preceded him.

No. Time to put on a brave face. I was happy at school. Really. I didn’t dance a jig of joy when I heard that the College was closing. I don’t wake up in the small hours, sometimes, often, fleeing my tormentors, recoiling from their blows. When I press myself against your warm, forgiving body, it’s not that I need sanctuary. Honest.

My tormentors. By which she usually meant the older girls. Christine Amberleigh. Isabel Chappell. Susan Balmain. The others. Those girls. But what of the ones whom she herself had tormented, as she’d tried to impress, to be welcomed as one of the in-crowd? Did they still dream terrified dreams, she often agonised, when she gave in and allowed her mind to wander back.

And what of the members of the Common Room?

What of Mr Gillespie?

All of the ghosts, assembling to confront her once more. And Gillespie’s at the head of the queue.

The car scrunched over the gravel, bringing her back to reality. “You can’t…” she started, before interrupting herself: the glistening Jaguars and BMWs of today’s guests could, of course, park in one of the hallowed spots that were formerly the domain of the senior members of the common room’s battered old vehicles. Daddy used to be made to park by the stable block: it kept the girls and their tearful farewell embraces out of sight, out of mind. Only her embraces were never tearful: Daddy was too oblivious, she was too embarrassed. She kept her sobs for the dormitory and the dark.

It must look impressive, she guessed, if you hadn’t seen it before. The imposing Victorian mansion; the glimpse of the formal gardens; the age-old chapel, rebuilt by Wren in the days when the estate had belonged to Lord Chadwick.

Tom smiled happily at her – checking that his girlfriend was glad to be back. She couldn’t tell him: she was a confident young woman now – happy, Miss Successful. She’d made the effort. Conquered the shyness, overcome the hurt. No longer the small, lonely child. At least on the surface.

Her took her hand, smiling happily to himself. His good idea. His little adventure. “Paradise regained, eh?” he teased, squeezing her, as he led her once more through that front door.

The hotel reception. The school admin office. Cold, as ever. The little girl, standing there, yellow slip of paper from her housemaster in hand, waiting for the school secretary to reach down the leather book and transcribe the details. The braver adult, smiling weakly as the receptionist welcomed them. Asked if they’d stayed before as they signed the printed form (“Oh yes,” boasted Tom of the former victim who leant her head against him). Pointed them towards the stairs.

She stopped, abruptly. The trophy cabinet, silverware still gleaming. Still here? But of course – where else would they have gone? There can’t be much of a market for tarnished trophies from a tarnished school.

“Win any of those, my dear?” Tom enquired. She blushed as she pointed one out: the Hailsham Cup, still recognisable – would they let her get it out, she wondered, smiling for the first time. Her name carved out with those of the other Debating champions. The first, and still only, thing she’d ever won. Apart from Tom.

He tugged her on, towards the main staircase. A red carpet now, but the impressive (albeit slightly tasteless) stained glass still cast its colours across the hallway. Again, she hesitated.

“What is it, my love?”

She feigned a smile. “We weren’t allowed to use these stairs.”

Training runs deep, when breaking rules had such consequences. (He’ll be having me walk on the grass next, she reflected, almost allowing herself a smile. Almost.). Tom giggled, his adventure continuing.

Along the first floor corridor. Past the bedrooms carved out from the dorms in which the older girls chose their prey.

Past Dorm 3. Or, should she say now, room 14. But still the same walls which had watched her and Samantha Moran when they’d… explored. Touched, caressed, tasted; nervously, awkwardly, breathlessly. A wooden chair wedged bravely under the door handle as the others sat in prep. And their shared experience wedged between them thereafter: too embarrassed, too shy ever to repeat – or even acknowledge – their escapade.

Their allotted room was at the end of the landing. Bright, white. Quite as trendy as the papers had said. Unrecognisable. Yet unforgettably familiar; snipped from Dorm 5, where Isabel had taunted, Christine had hit. She drew the curtains, wanting to shut out the world – not wanting yet to look out at the playing fields, scene of twice-weekly humiliations almost as crushing as those of the bullies.

And drew the curtains because she wanted him. Needed him. Needed him to make her safe. Needed him to posses her – to punish her for her ungrateful thoughts. She undressed while he was in the bathroom, climbing under the soft down duvet, for once ashamed of her nakedness. Lay face down, buried in the pillows. Waited for him to climb in next to her. To feel her immobile, and climb on top. To take her, urgently: for his pleasure, this, not hers. To pause. Pin her wrists down. Then to possess his schoolgirl, deeply, intimately, in the way she so needed.

“Bet you never did this while you were here before,” he grinned afterwards. Not this, not exactly, she thought, remembering Sam Moran once again. Remembering Jason Walker, the groundsman’s son, up in Higher Stonehall Woods; she wondered what had become of him. If only you knew, dear Tom, if only you knew.

But, sated, he was asleep. His girl taken, job done.

She slid from the bed, leaving her lover to his snores and his dreams. The bathroom tiles were cold against her feet. She eyed up the deep bath, freestanding in the centre of the floor; they’d share that later, she thought, and then take each other once more. But now she simply wanted to shower, to try to wash away the memories.

Biggest improvement so far, she thought, as the hot water streamed down her, although the row of cold showers and shivering girls, watched over by the too-dutiful staff, might have made an interesting spectacle for today’s moneyed guests. How many of them realised what it had been like, she wondered, beneath the new and all too superficial gloss?

She dried herself quickly. Back in the room, Tom was dreaming deeply; she loved the way his limbs flickered in his sleep, cat-like. She steadied herself, closing her eyes, thinking, always thinking; if only she could stop. If only she could climb back in next to her protector; to safety; to love.

But there was somewhere she knew she had to go. She picked up her crumpled clothes, abandoned so hurriedly at Tom’s orders, and dressed.

Am I brave enough?

I need to see.

Do I dare?

I have to…

Hands trembling, she opened the bedroom door, and set off along the corridor. The stairs led upwards, towards more gleaming, polished rooms, before they twisted up one more, narrow flight.

She hesitated. And started to climb.

Aged fifteen, now. Palms sweating. Counting the stairs, willing them to continue for ever. Finding herself all too suddenly on the small landing outside her housemaster’s attic room.

Composing herself. Knocking on his door, softly. No answer. Knocking again, more forcefully: let me in. Let me flee.

The realisation that Gillespie wasn’t there. One-thirty, he’d said. After lunch. Not that she’d eaten. One twenty-nine now.

Minutes ticking by. Long, silent minutes.

The loneliest minutes in a girl’s life.

Contemplating. Regretting. Anticipating. Trying to imagine what it would be like; trying not to imagine too hard.

At last, hearing footsteps climbing the stairs. Standing straight, as if a correct posture would save her from harm.

Not him, though. Eleanor Cameron, instead. Lower Sixth; another star pupil. Two unfamiliar lunchtime visitors to these quarters, lining up, barely acknowledging one another, each lost in her own fears.

Heavier steps this time. Drawing near, in slow-motion. As though they were in a movie – although one in which other girls were supposed to star.

Gillespie scrabbled for the key in his coat pocket, and swung open the door. “I’ll speak to Miss Cameron first.”

Unfair, unfair, as the other girl brushed past. I was here first. Me, sir. Minutes more to fret – yet minutes more unscathed, too.

Through the door, she heard the murmur of voices, which fell into a long, ominous silence. A silence full of expectation, punctuated by a crack and an anguished howl. Her mind circled like a carousel, trying to picture the scene; trying to block it.

Four evenly-spaced whacks in all, each driving out its yelp of anguish and apology, then a silence once more. More murmuring… and then, before she knew it, the door was opening, and the first victim was making her escape, and she was passing – avoiding Eleanor’s eyes at all costs – and the door was closing behind her. And she was standing small in front of her housemaster.

“A petty act,” she heard. “Destructive. Infantile. Susan was most distressed”. Susan was distressed? About her books being left to soak in the shower? Susan, chief tormentor? And how did Susan feel when she was punching, kicking, scratching? But revenge was to have its due price: three strokes of the cane, recognising that she was a generally well-behaved girl who’d stepped momentarily out of line.

Her fingers trembled so much she could hardly manage to remove her knickers, before she bent over as instructed, lifting the grey skirt up and over her back, baring herself to him. “Touching toes without flinching”, as he whipped the rod down bringing pain as yet unimaginable, unbearable. The first stroke shocked her; the second astonished her; the third broke her, tears flooding out and shoulders heaving as she somehow maintained her stance.

And then she was on her way, shamed and shocked, punishment slip in hand. All done, all forgotten (although even as he said it, Gillespie must have known that not to be the case. Not then. Not ever.)

And now. What, a little more than a decade on?

The hotel guest lent back against the corridor wall, hands against the cool paint. Breathed deeply. Rubbed her watering eyes. She was almost congratulating herself on having brought herself back to confront the demons, when the door opened. Instinctively she stood to attention, but a smartly-dressed woman appeared: the same age, a little older perhaps, but somehow familiar. Looking at her with not a little concern and asking whether she needed help.

She forced a smile. “I’m fine. I got lost. It’s a bit of a warren, isn’t it. And all those stairs…” They nodded, they paused, and she was left alone once more.

She waited until the other woman was safely away, before heading back. Easier this time than then, when the veil of tears and the pain and the humiliation and her shaking legs had made the staircase harder to descend than a Himalayan peak. This time her backside simply ached from Tom’s ministrations, and her mind blazed merely (merely?) with her memories.

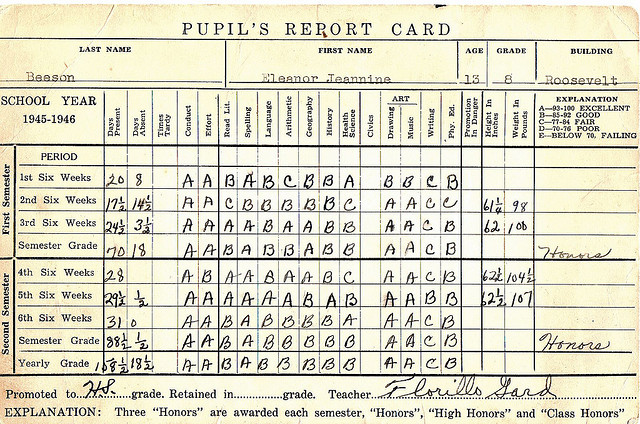

That time, she’d had to return to the admin office, the yellow punishment slip which Gillespie had completed to be passed to the curious secretaries to be recorded in the Punishment Book for posterity. (And what would have happened to the Punishment Book, she wondered, when the school was forced to close? Burnt, she hoped, with all of its shameful stories of bared backsides and bruised pride. Not in someone’s trophy cabinet, she prayed. God forbid, not still in the hotel).

This time, she could head back to the bedroom and strip to crawl in with Tom. That time, she had to lie face down on the hard dormitory bed, skirt raised, hands inside her panties, hardly able to touch the raised, burning skin.

This time, Tom reached a protective arm around her, too sleepy to notice the tears that flow from conquering demons. That time the tears were on all-too-public display. Taunts of “Look what we’ve got here,” echoed around. She remembered hoping that Eleanor, in another dorm along the corridor, was being cuddled and consoled; remembered wishing that they could change places.

At least some of the bullying had stopped; a caned paragon of virtue was at least a real girl. In her no-longer-iconic state, she’d found herself watching from safety as the bullies meted out their hateful treatment, no longer the one on the receiving end. After a few evenings as a spectator, she’d even – to her surprise, her shame, and her astonished enjoyment – joined in, using her wit to tease and taunt, the words scything into the victims even as she pummelled them. One of the gang, now.

After you’d been flogged once, so rumour foretold, future whippings no longer held the same terror. She could vouch that this was untrue: she’d been back in Gillespie’s study early the following term, howling her way through another dreadful six strokes. Six strokes for bullying, plus two more for flinching. “Obviously I was overly-generous last time,” he’d observed as she’d implored him for mercy. She’d cried like a baby for hours afterwards, less from the caning than from the guilt – her career as a wannabe bully now firmly ended.

But that was then, and this was now. And Tom was there, and was stirring, and was holding her and stroking her. He hadn’t even noticed that she’d been away. She’d never told him; never would. Couldn’t let down her guard, let the mask slip, reveal the fragile little girl underneath. Successful now. She’d survived. She’d won. Hadn’t she?

And after all, everyone enjoys their schooldays.

Don’t they?