It always amazes me when I read books and websites full of schoolgirl anecdotes. Every school with its ancient chapel, its hallowed cloisters, its beautiful playing fields and triumphs at hockey. Its dormitories, with young girls having pillow fights just as their predecessors had for decades before. Echoes of past glories in the framed photographs dating back to the late nineteenth-century. “Colleges”, named after ancient market towns – or in honour of noble saints (and even after some eminently forgettable ones). Prep, tuck shops, and Housemasters guiding their elite towards the heights of Oxbridge.

Real-life isn’t like that. At least it wasn’t for me.

Yet at least there were some parallels, some similar experiences for a bright, intelligent girl.

I say ‘at least’. Perhaps I should say ‘unfortunately’.

—

“Daddy wants a word.”

I’d heard the phone ring, of course. Hesitated to pick it up, whereas normally I’d have rushed to pick up the call in my parents’ bedroom. Heard mum’s voice from downstairs: “Hi, darling. How’s Singapore?”

Recoiled, slightly. I’d been watching the clock, wondering if he’d call, for three hours since I’d been sent home. It must be the early hours of the morning for him. After midnight, yet he always called once he knew I’d be back from school.

I curled back up on my bed, hugging a pillow tight. Heart fluttering, waiting, wondering what she was saying. What he might be saying in response.

“Daddy wants a word.”

I couldn’t move. Didn’t want to. Couldn’t face doing so.

“It’s costing a fortune, my love. Hurry up.” Unsympathetic, as she had been since she’d returned to find me at home, early, and I’d had to recount my tale of woe for the first time that evening.

I hesitated still, scarcely able to face the conversation. Partly not wanting him to know that I’d let him down, partly dreading his decision.

I padded barefoot into the next room, and picked up the phone from the midst of the clutter on my mum’s dressing table. “Hello, daddy.”

“Hi, my sweet. Missing you.”

I missed him too. Six thousand miles away: what right had his company to take him away from me? “Only three months,” they’d said. Only?

“I miss you too, daddy. I wish you were at home.” (Did I? Would I really rather have to look him in the eyes, to see his disappointment face-to-face?)

A pause. “Mummy told me what happened.”

The conversation rehearsed in my mind so many times these past few hours. My carefully-planned explanation. Yet the words came tumbling out: “It wasn’t my fault… I can explain… It was just a misunderstanding… She’s in the year above, she’s bigger than me… The teachers are just picking on me… It’s not fair.”

He listened patiently, waited for me to finish. Then paused again, a long pause this time. I wondered what he was thinking. I prayed he wasn’t too angry. Too upset?

“So mummy tells me that you apparently pushed this girl, then she pushed you, then you ended up fighting. And that one of the staff saw exactly what happened?”

“Please, it wasn’t my fault. She started it.” I sounded unconvincing, even to myself.

“But you ended fighting, nonetheless.” I could sense the disappointment in his voice.

Nonetheless. Guilty as charged. “Yes, daddy.”

“And so you were taken to the Headmaster?”

“Yes, daddy.” Marched down the corridors, the other girls watching, enthralled at the drama playing out in front of their eyes. Hauled into his office.

“And what did he say?”

“He asked what happened.” Mrs Pewsey, the grand inquisitor, outlining the case for the prosecution. The Headmaster, shaking his head in mock shock, probing for details.

“And mummy and I have to make a decision, right?”

“Yes, daddy.”

“And what will happen if we say ‘yes’?”

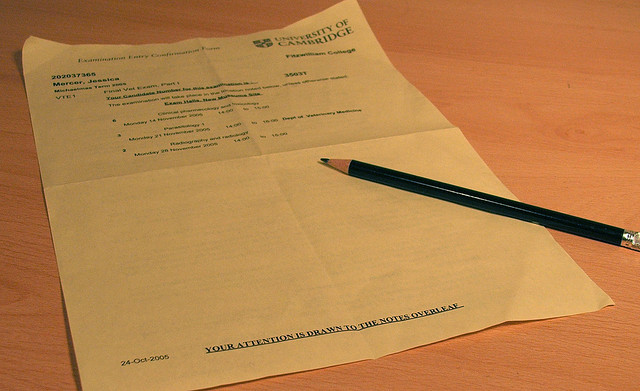

I swallowed hard. “Then I’ll have to go and see the Headmaster after assembly tomorrow morning to get the cane.”

“And if we say ‘no’?”

“I’ll be suspended for a week.”

“What about the other girl? What will her parents decide?”

Amanda? She’d been crying even harder than me when we’d left the Head’s office. “She… she’s been caned once before. So her daddy will say ‘yes’.”

“How many other girls in your class have been caned?”

I tried to picture the classroom, the girls sat at their desks. Nat, back in the very first term, for swearing at Mr. Wakefield. Erin and Caitlin for cheating last year. (Well, Caitlin hadn’t cheated, really; she didn’t need to. Erin was the one who’d done the copying). And then dear, sweet, Gemma, when they’d realised she’d been forging her sick note, just after we’d started Year 11 last month. I remembered comforting her at morning break afterwards, whilst some of the others teased, and the following morning too when she told me what had happened at home when she got home.

“Four.” Danger in numbers here. Please daddy, don’t make it five.

“And how many girls’ parents have chosen the suspension?”

I tried not to cry. “None…”

“I wish I were at home with you, my sweet.”

“I want you here so badly, daddy.”

“I’ll be back soon, my love, honestly I will.”

I was crying now, so much that I almost missed what he’d started to say. “…because you’d miss a huge amount of work if you were suspended. And the other girl – what did you say she was called? Amanda? – is going to get caned. And I wonder if it would really be fair to your four classmates if you didn’t take your punishment?”

I waited for the denouement. But none came. He was waiting for me…

“Yes, daddy.”

“And I so don’t want you to be hurt, but we’ve got to think about what’s fair, and right, and best for you in the long-run… What do you think?”

“Please, daddy.” Please… Come home. What do I think? Spank me yourself, if you must, like you did that one time on this very bed when Isla and I had been caught in Sir Hugh’s garden. Steal me away to another world, where everybody’s happy. Turn the clock back five hours. “I think… Daddy, I don’t know. I’m scared…”

“Tell me honestly, my love. I know it’ll hurt, but do you think we’d be right if we agreed to the cane?”

I wonder, looking back, if he ever heard my “Yes” through my sobs, before he told me how he’d fax a letter over to the Headmaster. It didn’t even occur to me until much later to wonder whether he’d been able to fax it himself from his room, or whether some hotel worker had been party to my shame.

And so I agreed to go to the Headmaster in the morning. Promised him that I’d be brave. (Brave? Me? No way. But I’d try, I really would).

“My sweet?”

“Yes, daddy?”

“You know that nothing that ever happens will make me think any differently about you, or make me love you an iota less?”

“I love you daddy.”

“I love you too. I’ll be thinking about you.”

And then he made me give the phone back to my mum.

My bedroom’s nice. I love my posters, my teddy bears. It’s safe. Just the sort of place I needed to curl up and cry. I don’t know what generated the most tears: Daddy’s resigned, disappointed tone; the sheer humiliation; or the dread of the pain to come? I remembered how it had hurt that time, when he’d taken me over his knee, and his big hands had imprinted his punishment. But the cane? I thought back to poor Lisa McBride, and her howls as she’d been thrashed on the stage in front of the whole assembly that time for stealing those phones: was that really going to happen to me?

I hardly slept that night, as you might imagine.

—

Mum tried to avoid the issue in the morning, as I knew she would. It could have been any other school day, for all she said. I guess she didn’t really know what to say. (Remembering back to a conversation I’d once overheard between her and Aunt Erin about the priests at their school, and their straps, perhaps she just didn’t want to think about it).

And it could have been any other school assembly – the same dull reading by an A-level pupil of a worthy yet incomprehensible poem, an uplifting song from the discordant school choir, an interminable list of announcements about the minutiae of school life – were it not for the thought of what was to come. Were it not for the fact that the Head’s final, “Any girls who need to see me will find me in my study immediately after assembly.” And for the fact that my very presence in the Hall, testament to my parents’ decision, provoked glances and giggles in my direction.

Amanda and I found ourselves walking towards his study together, footsteps echoing around this far end of the top floor corridor usually out of bounds to mere minions unless they’d particularly excelled, or particularly disappointed. The older girl gave me a hug, enmity replaced with the need for mutual re-assurance.

We knocked on his door.

I don’t know why, but as I’d fretted and panicked last night, turning the likely scene over in my head (trying to imagine, even as I tried to forget), it had been Amanda who’d gone first. She’d had it before; she was in the year above. She was altogether bigger and braver and more confident. So when he looked at me, his “would you join me first” ran through me like a bolt of lightening.

The room was bare, cold. His desk was pushed against the wall to the left of the door, papers moved to one side. A solitary wooden chair, curved, with arm rests. A few framed photos on the wall; overflowing filing cabinets, a dusty silver trophy abandoned in a corner (presumably a leftover from the establishment’s long-forgotten grammar school days). He didn’t even sit down, taking the cane straight from his desk and inviting me to lift my skirt and bend over the back of the chair. I did so nervously, the wood cold against my exposed thighs, hands resting on the cushion. Acutely conscious of feeling almost bare: I could swim happily in a fairly immodest bathing costume for the school team in front of dozens of spectators, yet my white school knickers now left me feeling naked.

He spoke calmly, in his usual measured tone. “I received your father’s note this morning. He sounds as disappointed in you as I am. As it’s your first time, I shall be somewhat lenient, yet I shall have failed in my job if I don’t punish you hard enough to prevent your return. Three strokes: count them as we go.”

I said that I’d tried to imagine, the previous night, piecing together anecdotes and the memory of Lisa in the school assembly. Nothing, and I mean nothing, could have prepared me for the pain of that first stroke. For a moment, a fraction of a second, I thought it was even bearable – a hard blow, the stick drumming into me; a thud, no more. But then the pain, searing across my behind, like nothing I’d felt before.

Be brave, daddy had told me. Be brave.

I became conscious of the Headmaster watching me, and recalled his edict to count. “One, sir.”

The second followed shortly. And if I’d thought I’d known what to expect, I’d been dreaming: this second blow built on the first, the pain crescendo-ing out of control.

I gasped, gulping for air, somehow acknowledging that he’d reached “Two.” Clutched the cushion, knuckles white, concentrating.

And then it was over. God, the third stroke hurt, even more than the third, the dam that had been holding back the tears giving way, but then I could proclaim my, “Three, sir, thank you sir, sorry sir” and be standing up.

“Wait for me outside, and send Amanda in. I’ll want you back in a moment when I’ve dealt with her.”

We passed in silence, avoiding each other’s eyes. Not sure what to do: etiquette books should have a section on “How to behave after a caning.” Hands on my backside, I leant against the wall, hoping that might quell the pain.

And then the first of Amanda’s strokes, as clear as can be through the plasterboard wall behind me. Heard her cry; realised that my own punishment must have been equally audible.

Tried not to listen to strokes two and three as I tried to stem the flow of tears.

And listened aghast as a fourth howl came from the room behind, and then (quickly this time) two more loud blows. Six? But why? I’d had three? And how they hurt. Poor Amanda. What…?

The door opened, and he called me in, cane still in hand. She was standing there white-faced, bawling. I wanted to hug her – for her sake, and for mine. My own sobs started once more.

The Headmaster looked from one of us to the other, no doubt contemplating a job well done. “So you’ve had three strokes each for fighting. Amanda was given an extra stroke for starting the fight, as Mrs Pewsey confirmed to me yesterday, and she’s taken two extra since this is her second caning.” He looked at me: “Let that be a warning to you not to re-offend. And I doubt you’ll be back here in a hurry, Amanda.” (As if I needed a warning. As if she did).

“Sorry, sir.” From both of us. Sorry girls indeed.

“OK, on your way. You may stop and wash your faces, but I shall check with your teachers that you were back in class by…” he looked at the clock, “9.20 at the latest. Five minutes, or you’ll be back here at lunchtime. Now hurry.”

“Yes, sir.” Again in unison, no desire to be back here at lunchtime or at any time.

—

Daddy came home about a month later. The scars had healed by then, of course – at least the physical ones: being fair-skinned, the three stripes marked me for more than a week.

But the mental ones? When he arrived back, it was hard not to remember that there was some unfinished business to discuss. He swept me off my feet, of course: he always does. Hugs, and kisses, and an evening of not wanting to let him go. My daddy, at home, with me, where he should be.

And we talked – about Singapore (silly things: how he’d been caught in a thunderstorm and drenched from head to toe; how the maid who’d tidied his hotel room every day had laughed when he bought her flowers at the end of his stay). About school – how my work was going, what the other girls were up to. About everything but…

And when I went to bed, curled up in my pyjamas, reading light on, he came upstairs – as I knew he would. Perched on my bed. Held me tight, warm, close. Secure. And then we talked – about what had happened. How he’d worried about me. About whether it had been awful, whether it had hurt, whether the other girls had teased (yes, yes, and unequivocally yes).

Talked about no matter what happened, I’d always be his most precious thing. How he loved me. How he was home. How he’d look after me, always.

I cried a little, and he wiped away my tears, and kissed me goodnight. And I cuddled up into his embrace, safe and warm, and feel deeply asleep